Investing in inclusion: financing disability-inclusive education

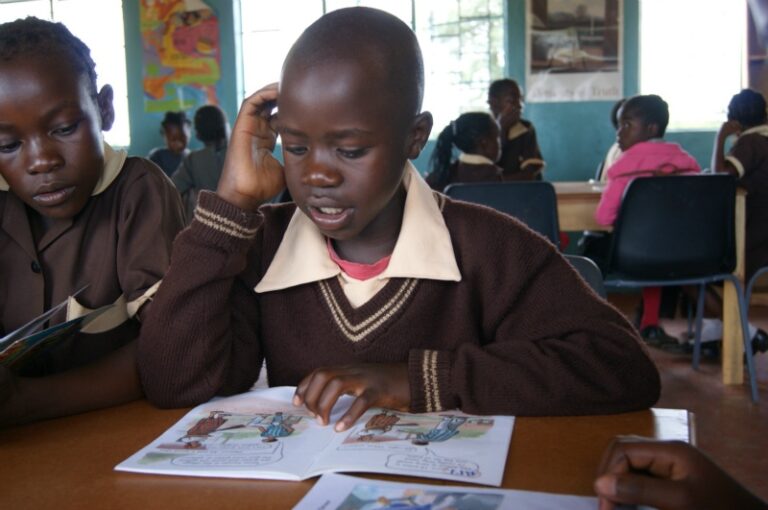

Despite global efforts to create more equitable education systems, access to education by persons with disabilities, especially in low-and middle-income countries, remains inadequate. It is estimated that, globally, between 19 and 35 percent of children with disabilities do not attend school. Not only does this harm the development, wellbeing, and income-earning potential of individuals and increase the financial burden on families, but it also hinders economic growth.

Education funders have a key role in contributing toward creating more equitable education by providing resources and support to ensure access and opportunities for all learners. However, costing, budgeting, and financing disability-inclusive education comes with specific challenges.

In this blog, we share our insights into some of these challenges, as well as suggested solutions, gained at a recent workshop we attended on Financing Inclusive Education hosted by The Brookings Institution‘s Center for Universal Education in collaboration with the Special Olympics and the Global Partnership for Education. The workshop was part of Brookings Institution’s Symposium on education systems transformation for and through inclusive education.

Benefits of investing in disability-inclusive education

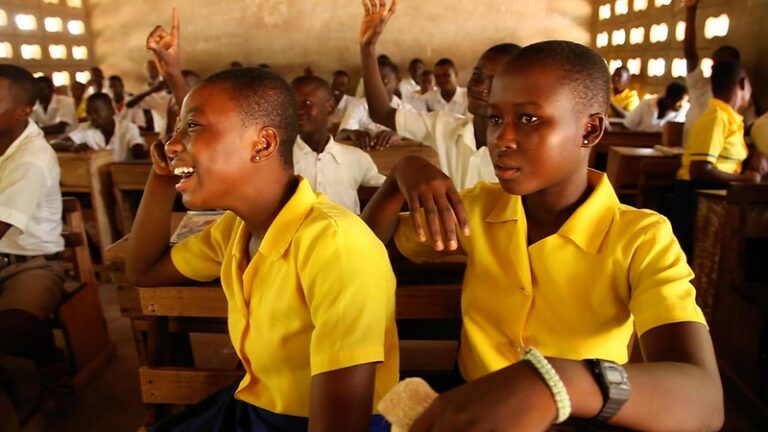

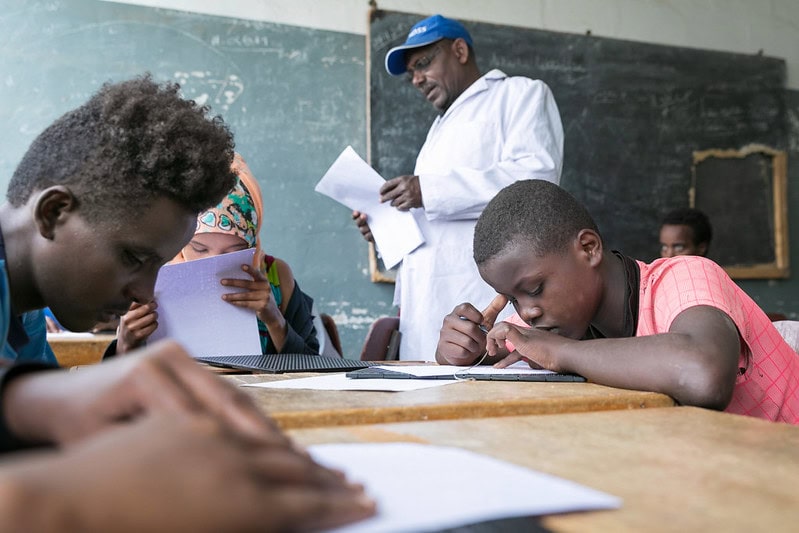

Disability-inclusive education ensures that all children, regardless of their disabilities, have equal access to quality education by removing barriers, providing support and accommodations, and fostering an environment of acceptance and diversity within educational settings. This fosters social inclusion, enhances independence, expands opportunities for employment, and promotes overall well-being and self-fulfillment.

Investing in education for persons with disabilities yields positive returns in terms of improved employment opportunities, higher earning potential, enhanced quality of life, and reduced reliance on social welfare programs. Research in Nepal has shown that the estimated rate of return to investment in education for persons with disabilities ranges from 19.4 to 32.2 percent, which is significantly higher than the rate of return for persons without disabilities, estimated at a global average of around 9 percent.

Ensuring access to education for children with disabilities also benefits their families. Education empowers children with disabilities to develop skills and independence, thereby reducing the need for caregiving, which often comes at a high cost to families, particularly for women. A study in Uganda showed that households caring for a child with a disability faced economic burdens exceeding the national average household expenditure, with an annual cost of illness that can surpass 100 percent of the national GDP per capita. The findings revealed that 84 percent of caregivers faced catastrophic expenditures leading to coping strategies such as selling their property, reducing food consumption, and/or borrowing money.

Enabling children with disabilities to find employment and earn an income has macroeconomic benefits too. According to a report from the International Labour Organization (ILO), the economic impact of excluding people with disabilities from the workforce is estimated at between 1 and 7 percent of GDP. This figure represents the difference between the income of people with disabilities and what they would earn if they didn’t have disabilities.

Tracking funding for disability-inclusive education

While governments and households are primary sources of funding for disability-inclusive education, only 2 percent of international aid is allocated to projects with disability components, with just 8 percent of this going to inclusive education.

Philanthropies play a growing role in funding education pilots and innovative projects, with $2.1 billion contributed to education between 2013 and 2015. However, the scale of their direct support for disability-inclusive education is unclear. NGOs like Save the Children, Christian Blind Mission, and Humanity & Inclusion are also important players in this space, channeling over 75% of disability-inclusive aid since 2014 (compared to 30% of all aid).

Disaggregated information about budget allocations and expenditure for disability-inclusive education is scarce, making it challenging to assess whether spending is sufficient and to hold governments and donors accountable. This is particularly challenging in relation to the twin-track approach embraced by some global actors, where one track aims for broad inclusion of persons with disabilities in mainstream development programs, and the other track targeting disability-specific interventions.

Strategies to improve disability-inclusive education financing

While ensuring an adequate level of funding is a critical step towards achieving equitable education for learners with disabilities, there are several strategies funders can pursue to improve the efficiency of existing resources and achieve the most impact possible for each dollar spent:

Designing for inclusivity: Incorporating Universal Design Principles into curriculum and system development to ensure accessibility for all learners from the outset can minimize the need for costly retrofits or specialized services for students with disabilities. By designing educational environments, materials, and technologies to be accessible to a wide range of learners, schools can make more efficient use of resources and potentially lower overall costs associated with providing inclusive education.

Tackling the date challenge: Lack of costing and cost-effectiveness data is a frequent barrier to disability-responsive planning and budgeting. In many countries, there is an incomplete picture of prevalence rates, enrollment, completion rates, etc. of learners with disabilities, and there are no systematic global resources to inform the costing of disability-inclusive education. These challenges can be addressed by creating guidance and tools to improve data collection and analysis, and for allocating resources within the twin-track approach.

Decentralizing education funding: Increasing the autonomy and accountability of sub-national authorities through decentralized funding mechanisms can make resource allocation more effective by enabling support to be tailored to local contexts. However, it’s important to note that decentralization often means that education policies and practices vary between regions or even individual schools, which can lead to inconsistency and inequity in access to services.

Access to education is not only a human right for persons of all abilities, but also an economic imperative to build prosperous societies everywhere. Governments, donors, philanthropies, and NGOs must work collaboratively to develop approaches, tools, and systems to improve planning, budgeting, and financing of disability-inclusive education worldwide. USAID’s Financing Disability-Inclusive Education White Paper provides a useful framework for planning and coordinating action to finance disability-inclusive education at a country level, and a set of recommendations to catalyze global action.

Speakers at the event included representatives from the Global Partnership for Education, University of Tsukuba, The World Bank, USAID, Sightsavers, and ATscale, the Global Partnership for Assistive Technology.