Insights from CIES 2024: Key issues surrounding non-state actors in education

At the recent CIES – Comparative & International Education Society conference (CIES 2024), the Education Finance Network convened three panel sessions in collaboration with several of our members. In this blog post, we share some of the insights gleaned from these sessions on key issues surrounding non-state actors in education today.

Over 70% of children in Lagos are educated by non-state schools

In a panel on “Fostering effective and enabling regulation of non-state schools” – with Global Schools Forum, SEED Care & Support Foundation, and EDC (Education Development Center) – we learned that Lagos, Nigeria, has one of the largest non-state education markets in the world, with 88% of all primary schools and 78% of all junior secondary schools operated by non-state providers.

However, only a fraction of these schools are officially registered, which creates obstacles to their involvement in education policy planning and implementation. Their absence of engagement with the government via registration contributes to a lack of support by the Ministry of Education for school improvement initiatives, which in turn results in low educational quality across many of these schools. Global Schools Forum and SEED have found that low-free non-state schools across low- and middle-income countries are often discouraged from registering due to complex requirements, burdensome processes, and high fees.

SEED has developed a Quality Assessment Tool (SQAT) to address these challenges by helping non-state schools assess their quality and providing a pathway for improvement. The tool breaks down the concept of ‘school quality’, which can be difficult to grasp and act upon, into smaller, more manageable components that can be addressed through simple interventions. Government approval requirements and regulations are embedded in the indicators to support schools with regulatory compliance.

Balancing considerations of cost and quality of education initiatives

A panel on “Scaling and sustaining private innovations in public education systems” – with Higherlife Foundation, Innovations for Poverty Action, and FUSAL – ignited a discussion around balancing the effort to reduce the cost per child of educational interventions, versus the endeavor to ensure a high quality of the solutions delivered.

When seeking to scale interventions in low-resource settings, keeping the cost per child low is often deemed necessary to ensure government uptake and sustainability. However, one participant argued that it’s paramount that any discussion around cost and cost effectiveness does not lose sight of the fundamental right to quality education for all children, regardless of their socio-economic status. Efforts to provide cost effective interventions must not overshadow the broader need for greater investment in education in low- and middle-income countries. Whilst cost data is useful to ensure that interventions can be scaled and sustained within limited budgets, increased transparency around costing can also help reveal disparities in global spending, which in turn can stimulate discussions about the ethical imperative to deliver quality education.

Navigating the transition from innovation to government adoption

For actors aiming to scale education innovations, deciding when to transfer an intervention to the government is a question that involves both political and technical considerations.

From a political perspective, securing and sustaining government buy-in is crucial and may require aligning with shifting priorities and navigating political cycles. Managing diverging national and sub-national political cycles adds complexity but can also help maintain continuity of a policy as sub-national governments can continue implementing existing policies even if there’s a change at the national level.

From a technical perspective, it’s important to consider the government’s capacity to replicate the intervention’s theory of change. Governments need robust monitoring and evaluation systems to understand how the different outcomes of the theory of change have been achieved during the pilot, and to allow them to replicate the components of the intervention.

Another perspective suggested that successfully transferring an intervention to the government need not entail a strict replication of the initial pilot. Instead, it may involve adjusting interventions to suit local contexts, while carefully identifying which specific activities are most pertinent for achieving positive outcomes.

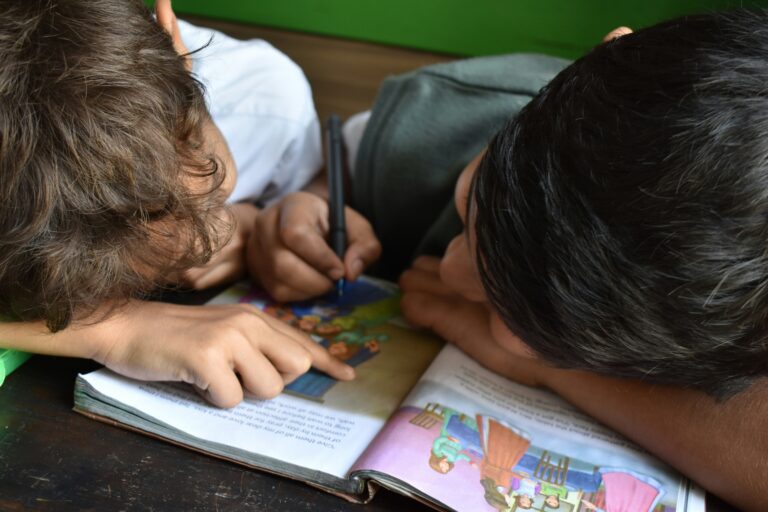

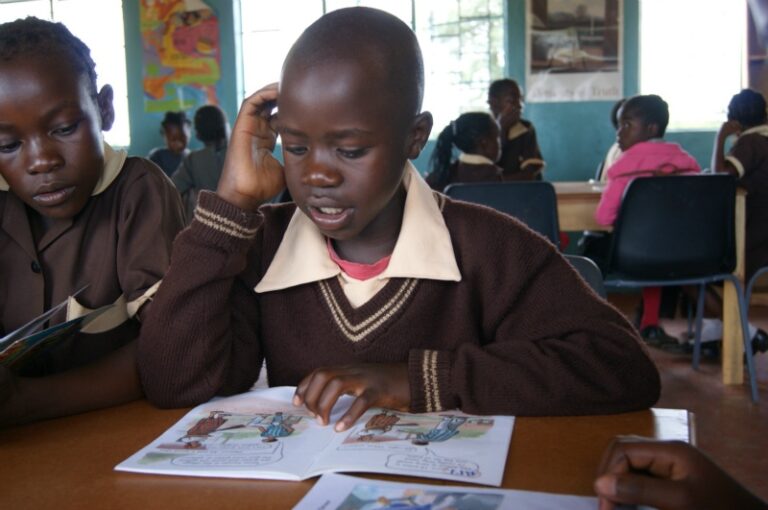

Exploring different approaches to reach underserved communities with EdTech interventions

In a session on “Unlocking the potential of EdTech for effective learning by engaging communities” – with Worldreader and EIDU – Worldreader discussed strategies to reach users of BookSmart, their reading platform for children and parents. Worldreader employs two main approaches :

- Through partnerships with community based organizations (CBOs), BookSmart is directly introduced to parents and caregivers by a local organization they know and trust, and which provides different levels of support, such as WhatsApp messages, assigned reading, training sessions, and guided shared reading sessions.

- Through partnerships with telecommunications companies, BookSmart is promoted for readers to access on any device, in some cases with subsidized mobile data for costless access to reading.

When comparing engagement and retention levels between these approaches, Worldreader has found that partnership approaches with telecommunications providers subsidizing data may lead to more consistent and longer-term reading habits. Conversely, programmatic approaches with CBOs tend to result in intense reading during the program’s duration but may decline after the end of the program without ongoing support provided.

Interestingly, a session participant shared contrasting experiences related to user engagement in India, where partnership approaches with telecommunications companies led to declining engagement, while partnerships with CBOs resulted in more sustained engagement. This variation may be attributed to differing mobile data costs, cheaper in India than Sub-Saharan Africa, which may influence the effectiveness of data subsidies.

The importance of understanding the context was also highlighted by EIDU, whose iterative design process involves defining the problem, creating prototypes, and testing them with users to ensure effectiveness. Starting with prototypes, the team asks for feedback before proceeding to testing, which eventually leads to AB testing in schools. This design funnel ensures that the solution aligns with the actual problem and user needs, with a focus on testing assumptions around engagement drivers and barriers.

Fostering learning, sharing and collaboration

The highlights shared in this blog underscore the critical role of non-state actors in improving access to quality education for children across the world, and the challenges and opportunities they encounter in doing so. As a network convening a broad spectrum of non-state actors, including funders, researchers, implementers, and ecosystem builders, the Education Finance Network will continue to facilitate learning, sharing, and collaboration to improve education systems worldwide.